Squished: By Death

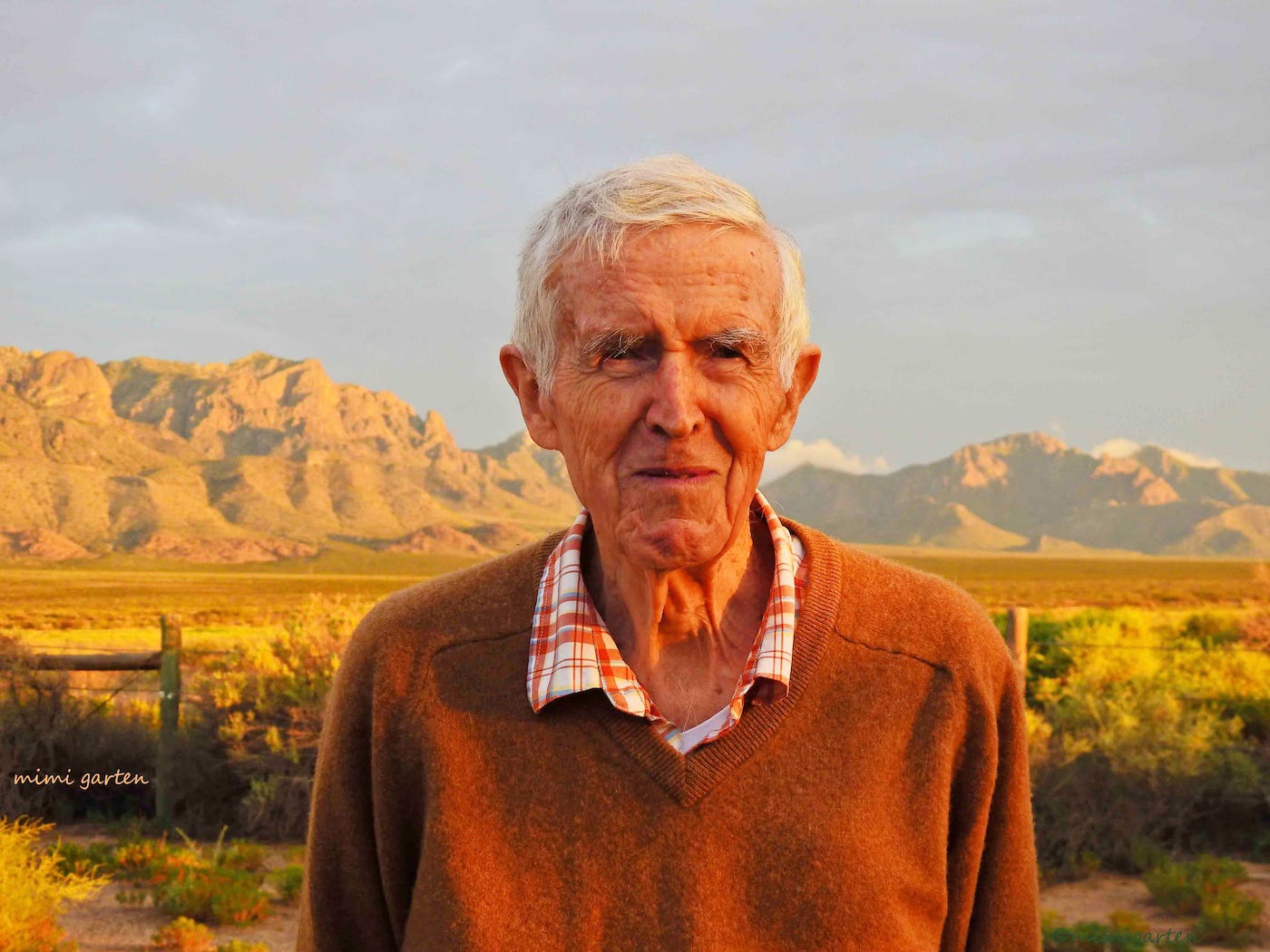

So, my dad died.

At first I thought: I can write about this. Then, as the weeks slid by and the grief became less a feeling than a new continent where I now lived, I thought: Fuck that. I can’t. No.

Then, about three months into Grief, the New Continent, the Red Hand Files #286 landed in my inbox: Nick Cave again reminding me, and all those who are stuck or afraid (or both), that life matters more. So I decided it didn’t matter which saddle, I had to get back on the horse.

Here is Death in 4 Acts. More or less. They’re not linear. If you don’t like one you can hop to the next. Or click elsewhere. I don’t expect people to read this. But I needed to write it. And I was able to believe myself that it was reason enough.

“Hospice”

Shortly after I wrote that post in March about all the mayhem in the hospital, we tried to get Dad moved to a hospice. But it was too late. The doctors now said he was “actively dying,” and he couldn’t even be transferred to another floor. So they created a hospice-like environment on the ward where he was to end his days.

It was funny — in the unfunny way our medical system gets (almost) everything wrong. Because: nothing changed. Dad was in the same room, in the same bed, with the same gown, the same tubes.

Except now — under the soft, fluttering banner of Hospice — everyone started being really nice to us. I wanted to cry with relief. And I wanted to scream the place down to rubble.

From brusque and too-busy-for-you, the doctors became quiet and solicitous . I think they made eye contact. The nurses lingered by Dad’s bed, or met us in the hall and told us stories about their own parents’ passing.

My brother and I had an in-person meeting with the social worker and some other hospital people, where we sat together for 15 or 20 minutes and — if memory serves — we talked! To each other!

Now Dad’s comfort was paramount. No more talk of tests or medication. The idea that Dad also could have been comfortable for the previous eight days instead of miserable, as he managed to spit out at one point — was never acknowledged.

Why? How come not one doctor ever looked at my 92-year-old, emaciated dad in the week before he died and said, “Hey, call me crazy, but maybe we could make this guy comfortable?”

I subscribe to JAMA now (Journal of the American Medical Association). I’m waiting for someone to write an exposé: Systemic Sadism: How and Why Pain and Discomfort Are Prolonged in Clinical Settings.

I’m not just being a jerk. I’d love to know. I’d love someone with 18 letters after their name to explain why the “treatment of illness” has become utterly divorced from the care of the patient. Please? We’d all feel so much better if we knew.

Death Bonding

A couple of weeks ago, my husband and I had dinner with friends — folks we hadn’t seen since my dad’s death. When we all sat down at the charming but somewhat overpriced West Village restaurant, I said the words that are more or less the same ones I say in most social situations now:

Let’s talk about death. Do you mind? It’s really the only thing I can think about.

This seems reasonably selfish to me. Plenty of people take over a conversation with some humble brag or big news, forcing everyone to exclaim and seem pleased while the exciting event is unpacked for the first third of the meal. Why not put Death on the table then?

I think most people are grateful. Uncomfortable. But grateful.

Really. If you open your mouth and say almost anything in that realm: “Blah blah blah DEATH blah blah blah,” I find that most people grab the baton and run with it.

I was on a work call not long ago with a person I didn’t even know that well, and — God knows what prompted me — I said some of the things I’ve been saying: “Blah blah blah DEATH blah blah blah.” And this person replied, without missing a beat, as if I’d mentioned the cost of my SweetGreen salad, “Oh yeah. I’ve got my dad’s cremains right here on a shelf. I like to look at the urn. It’s comforting.”

Then we both laughed and talked about cremains and dead fathers, and then, because we didn’t actually have that much to say, being relative strangers except for the commonality of having dead parents, we got back to work.

My Death

A strange thing happens when Death swings by. When you’re quiet, you can feel the soft brush of His wings on your neck. Reminding you: Was that breath your last?

Or this one?

For a few weeks after my father died, I knew Death could hear me breathing, I could feel Him waiting. At those moments I prayed: Not me, too. Not now. Not yet.

I told myself this was normal. You lose someone so close, someone whose own breath you’ve watched and waited on, of course you’ll hallucinate all kinds of things.

Then, I watched The Seventh Seal with my husband. If I could make a suggestion to anyone in the early stages of life after death: Don’t watch The Seventh Seal. I think my husband thought it might be cathartic — and it was gripping and weird and dark in all the ways I love — but it also convinced me that Death had his arm around me.

Then I went to see Grace, who cuts my hair. I told her that I thought I might die. (Well, she and I do have pretty deep conversations, though prior to this we mostly talked about our kids.)

She got really alarmed. I mean: Very. “Are you … depressed?!” she asked, in the tone of someone asking whether you had the plague, and might actually die right then.

I didn’t know how to answer her. It hadn’t occurred to me that I might be depressed, not just grieving. “Maybe,” I said.

She nodded and looked less spooked now. “I think so. Maybe a little.”

“I’m OK, though,” I reassured her. I felt that even Grace, who wears her soul on her sleeve, needed my reassurance.

I’m OK, You’re OK

I’ve spent a significant chunk of this mourning time telling people I’m OK. “Better now.” They need to hear it. I’m not sure why. What would happen if I said, “Still terrible”?

After a certain point (when exactly?) you do start to feel as if you’re draining people’s batteries.

Or you’re adding to their own fear that grief lasts far too long.

Or you remind them of a grief they’d hoped to forget.

One person told me that they hadn’t had time to grieve their parent’s death. It happened during Covid. They couldn’t be at their parent’s bedside. Everyone was frightened. “I should have taken more time,” this person said. “I still regret it.”

I was pained by that — the idea that the death of someone you love can be over, packed up in a box and put away (is that the symbolism of burying our dead?). I wanted to say, It’s not too late! You can still grieve! But I don’t think that’s what they wanted to hear.

If I’m honest, telling other people I’m OK is as much for me as it is for them. Mostly because if you tell the person who’s inquiring: Yep, I’m all right, they won’t ask too many questions.

It’s not fair, is it? Sometimes you do want questions. (Doesn’t anyone care?!) Sometimes you don’t. (People are so intrusive!) Sometimes you have a moment with people who are skilled at asking the right thing, or in a kind tone — while others are not — and there’s no way to prepare yourself.

I was at a gathering a few weeks ago, and a friend’s son asked a beautiful question: “Do you light a candle for your dad?”

I do! I hadn’t told anyone that. I was so touched that he’d asked. That it came to him, to ask that. I thanked him, really meaning it. But I also understood he had no way of knowing that he’d just done such a good thing.

I can completely empathize with your experience. It’s hard enough to lose a loved one but the health care system adds another level of trauma to the whole ordeal. Take it one day at a time.

Your essay is deeply moving and bravely honest. It captures the complexities of grief with raw emotion and sharp insight. Thank you for sharing such a personal journey